Braco Dimitrijević (1948), born in Sarajevo, is one of the best-known Eastern European representatives of the conceptual art which flourished in the nineteen seventies. Dimitrijević was very young when he wrote a fairy tale about the chances of becoming an artist. The story, made into the Hollywood film Great Expectations, tells of two mythical/imaginary painters, one of whom by chance becomes acquainted with a king looking for his hunting dog. The king takes the fortunate artist, Leonardo da Vinci, into his court, but the name of the other, equally brilliant but undiscovered painter is not retained by the defective memory of the people. This bitter parable draws attention to the illogical, random course of art history. But Braco Dimitrijević has shared Leonardo’s fate: through his painter father he worked with oil paint even as a young child, and as a young man he was admitted into high intellectual circles. He now lives in Paris and Zagreb. This large-scale exhibition at the Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art will let the Hungarian public see for themselves the work of an artist who is always contending with chance, whose consistent conceptual oeuvre is based on a strong critical attitude, installations and photo-documentation.

Having broken with the traditional frameworks of painting, Dimitrijević took to the streets in the nineteen sixties, and later proclaimed, “The Louvre is my studio, the street is my museum.” His first “accidental work”, the cloud of dust through up by cars from sculptor’s plaster scattered on the road, was made in 1968. Then he placed a bag of milk on the asphalt, and got the driver to sign the remains spread over the road, from which the work Painting by Krešimir Klika was born. So the “accidental painting”, which did away with abstract expressionism and the cult of genius, got an “accidental artist”. Dimitrijević took this even further: in 1971 he hung up three giant black-and-white portrait photographs in the main square of Zagreb. On the façade previously covered with the portraits of party leaders, there appeared the gigantic portraits of three passers-by chosen completely at random, thereby completely confusing the people of Zagreb. The series Casual Passer-by later became Dimitrijević’ trade mark, a democratic celebration of the ordinary person which he has repeated throughout the world. The several-storey high, simple portrait photographs have over the last four decades or so appeared on the building of the Düsseldorf State Library, on the back of double-decker buses in London, above the Canal Grande in Venice, and on the walls of the Pompidou Centre in Paris. Dimitrijević is placing photographs of local passers-by on the facades of two Budapest museums in connection with the Budapest exhibition.

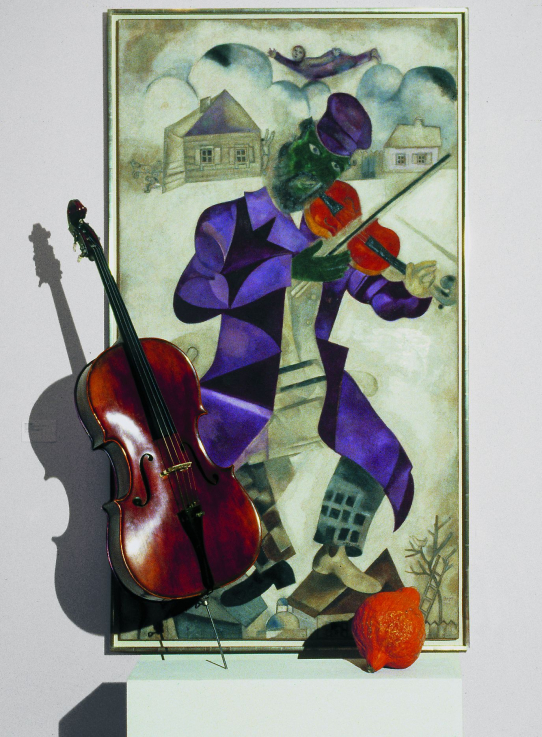

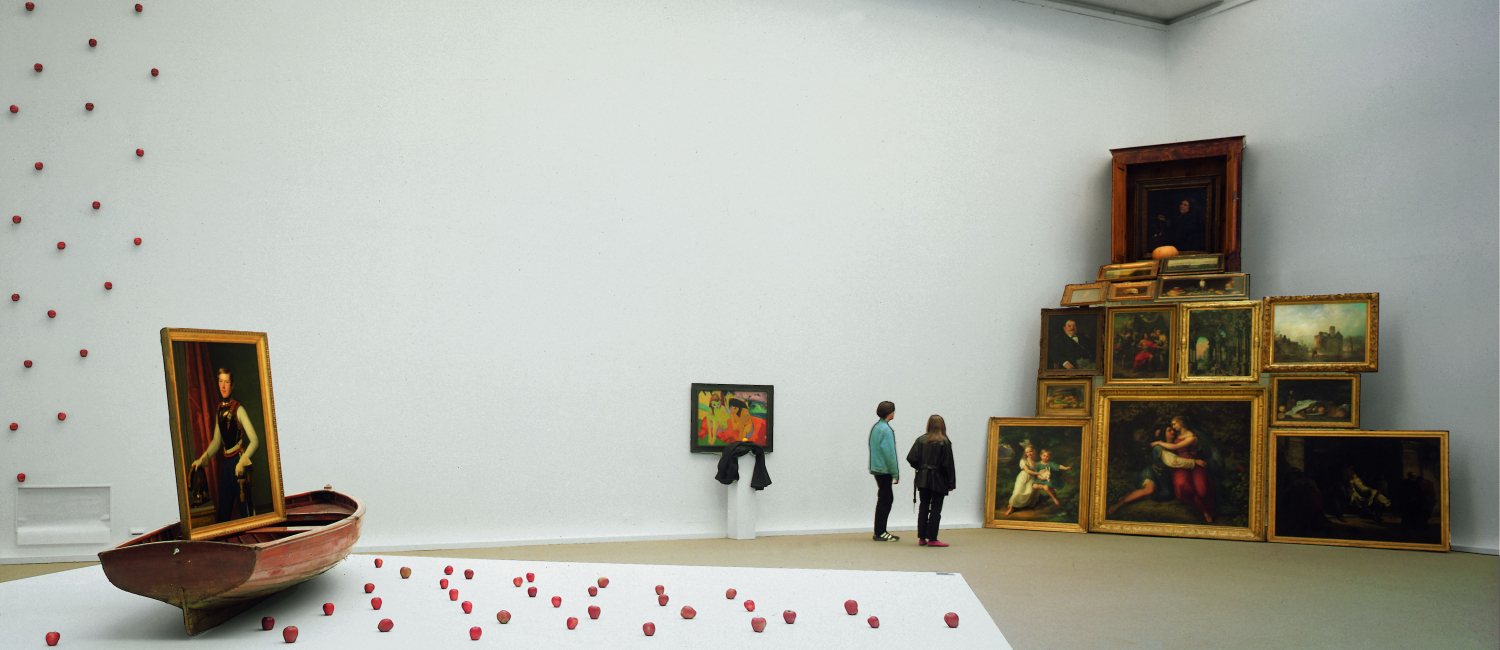

In 1976, Dimitrijević published his illustrated essay, Tractatus Post Historicus. “There are no mistakes in history, all of history is a mistake,” he wrote in what is in effect his artistic creed. He carved this fundamental slogan in gold letters on a marble pedestal called Post-Historic Landmark. Dimitrijević has constantly rebelled against the cruel selection of history, and in his series Transmonuments, made in parallel with the passers-by photographs, he parodies traditional monuments. He placed marble plaques at various points in cities with the inscription: “This could be a site of historic importance.” He named a street after an unknown person, erected a plaque to the birthday of a haphazardly-chosen passer-by, and sculpted the face of a person chosen at random and put it beside a portrait of Leonardo. In the early seventies he compiled his first three-component installation from a Kandinsky painting, an apple, and – of course – a portrait photograph of a passer-by. Since then he has made numerous triptychs involving masterpieces out of museums (Triptychos Post Historicus): he juxtaposed a Mondrian with an electric guitar and a banana, a Malevich with a bicycle and an orange, and a Leonardo with a hen’s egg and a fox trap. These installations, consisting of an art work, a natural object and an artificial device, were further expanded over the ensuing years. In his latest series Culturescapes, he brought wild animals together with classic works – both furthering and challenging the validity of traditional art. As he has often said, looking from the Moon, there is virtually no distance between the Louvre and the Paris Zoo.